Climate change is reversing U.S. air quality gains

After decades of progress in the U.S. toward cleaner air, climate change-related events will cause a steady deterioration through 2054.

Why it matters: An increase in large wildfires in the West, along with heat waves and drought, are already yielding a growing "climate penalty" to air quality, the new report finds.

- The effects of this penalty are not evenly distributed around the country, however.

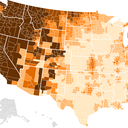

Zoom in: New research from the nonprofit First Street Foundation is part of a hyperlocal air quality model showing shifts down to the property level between 2024 and 2054.

- Its conclusions flow from methods contained in three peer-reviewed studies published by the coauthors. The report itself is not peer reviewed, however.

- The study finds that climate change is increasing the prevalence of two of the air pollutants most harmful to human health: particulate matter, commonly referred to as PM2.5, and tropospheric ozone.

- PM2.5 are tiny particles emitted by vehicles, power plants, wildfires and other sources. They can get lodged in people's lungs and enter the bloodstream, causing or exacerbating numerous health problems.

What they found: Through the use of air quality observations and the development of the new model, First Street's researchers found that the West will be particularly hard hit by increasing amounts of PM2.5 emissions, as wildfires become more frequent and severe.

- Already in California, the number of "green" and "yellow" days on the air quality index has decreased, with significant upticks in more harmful days.

- California's number of days with hazardous air quality (maroon) has increased by more than 1,100% since 2000.

- EPA data shows that in the West more broadly, orange air quality days exploded by as much as 477% between 2000 and 2021, the report states.

Of note: The research flags cities like Fresno, Sacramento, San Francisco and Seattle as being poor air quality hot spots related to wildfires and tropospheric ozone pollution.

- Future projections estimate a continued increase in PM2.5 levels by nearly 10% over the next 30 years, said Jeremy Porter, head of climate implications at First Street, tells Axios in an interview.

- This would "completely" erase air quality gains made in the last two decades, he said.

Between the lines: Porter says that whereas pollutants from cars and factories could be targeted by regulations over the past few decades (and the EPA is proposing tightening some further), climate-related deterioration in air quality is a much tougher problem to solve.

- Instead of national regulations, climate action requires global emissions cuts, and even sharp declines in greenhouse gas emissions may not alter trend lines for the next few decades.

The intrigue: The population exposed to "dangerous" days on the air quality index is likely to grow to 11.2 million between 2024 and 2054, an increase of about 13%.

- A 27% gain in the population exposed to "hazardous" (or maroon) days on the AQI is likely between the present climate and 30 years from now, the report finds.

- Porter said that while 83 million people are exposed to at least one "unhealthy" (red) day, this is likely to grow to over 125 million during the next three decades.

- While the West, particularly Washington, Oregon and California, are projected to see some of the worst air quality impacts, chiefly from wildfire smoke, other parts of the country are also vulnerable from heat-induced jumps in ozone concentrations.

What they're saying: "The climate penalty, associated with the rapidly increasing levels of air pollution, is perhaps the clearest signal we've seen regarding the direct impact climate change is having on our environment," Porter told Axios via email.

What's next: Porter said the new air quality model's findings have been translated into risk levels, known as "Air Factor," for individual properties in the U.S.

- The ratings will be available on large real estate listing sites.