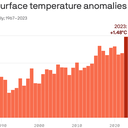

Earth's hottest year: 2023 neared critical Paris warming limit

During the hottest year on record, the global average surface temperature fell just shy of the 1.5-degree warming limit under the Paris climate agreement.

Why it matters: The climate of 2023 was the hottest seen in at least 125,000 years; for the first time in instrument records, some daily global average temperatures went well above the other Paris guardrail of 2°C.

Driving the news: Data released Tuesday morning from Europe's Copernicus Climate Change Service lays out just how many significant climate records were surpassed during 2023, amplified mainly by burning fossil fuels for energy.

The intrigue: Last year's heat raises questions among scientists about whether climate change has accelerated or even passed a tipping point. It started with a cooling La Niña event in the tropical Pacific Ocean and ended with a strong El Niño.

- El Niño events serve as added warming influences on top of human-caused climate change. But not even El Niño could fully explain the unusual warmth of 2023.

- Neither do other factors, such as the 2022 eruption of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcano in the South Pacific. That sent massive amounts of water vapor into the stratosphere that could be adding to short-term warming.

- One other suspect is the reduction of aerosol emissions from global marine shipping, but this too is thought to have contributed only a small amount to climate change during 2023.

By the numbers: The year had a global average temperature that was 1.48°C (2.6°F) above preindustrial levels during 1850-1900.

- Last year as a whole crushed 2016, which was the previous record in Copernicus' ERA5 temperature data set, coming in at 0.17 °C (0.30°F) above 2016's global annual average.

- June through December were the warmest such months on record, in some cases by staggering margins that themselves set records.

- July and August were the warmest two of any months on record, and the Boreal summer was the hottest summer yet recorded.

- December came in at a whopping 1.78°C (3.20°F) above the preindustrial average, Copernicus found.

Yes, but: The Paris Agreement's most stringent temperature target of holding warming to 1.5°C compared with preindustrial levels refers to a long-term, multidecade average, rather than a single year.

- Still, 2023 shows the world is already bumping up against the barrier established by diplomats at the Paris climate summit in 2015.

- In fact, Copernicus' report states it is "very likely" that a 12-month stretch ending in January or February will be the first such string of months to exceed 1.5°C above the preindustrial era.

- Many, if not most, climate scientists have concluded the 1.5-degree limit is likely to be exceeded, even over the longer term.

- However, temperatures can then be brought back down after overshooting 1.5 degrees, if emissions are sharply cut and existing greenhouse gases are removed from the atmosphere. This can happen through ecosystem processes and potential carbon removal technologies.

Between the lines: Small island developing states see the 1.5-degree limit as necessary for survival in the face of rising sea levels.

- In addition, studies have shown that the risks of climate change's potentially catastrophic impacts, from the collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to the loss of warm water coral reefs, escalate significantly if warming were to exceed 1.5°C.

What they're saying: "The extremes we have observed over the last few months provide a dramatic testimony of how far we now are from the climate in which our civilization developed," said Carlo Buontempo, who directs the Copernicus Climate Change Service, in a statement.

- "This has profound consequences for the Paris Agreement and all human endeavors."