Inside Russia's "filtration" system for Ukrainian civilians

Russian authorities have imposed a system of interrogation, detention and forced deportation for civilians in areas of Ukraine they now occupy.

The big picture: The U.S. State Department estimates that between 900,000 and 1.6 million Ukrainians, including at least 260,000 children, have been through Russia's "filtration" process, which Ukrainian and U.S. officials have said amounts to a war crime.

- Many of these children, including some taken from their parents, are believed to have been adopted by Russian families, according to multiple reports and human rights groups.

- Many adults — particularly those suspected of working with the Ukrainian army or nationalist militias — are believed to be in Russian detention camps in eastern Ukraine, a recent U.S. intelligence assessment found.

Taras Ulyanchenko, a 21-year-old student from Mariupol who went through the filtration process, was more fortunate. He was ultimately able to leave Russia, but only after detention, intense interrogation and a long and stressful journey.

- Speaking to Axios via multiple video interviews, Ulyanchenko gave the "Axios Today" podcast a harrowing account of his experience through Russia's filtration system.

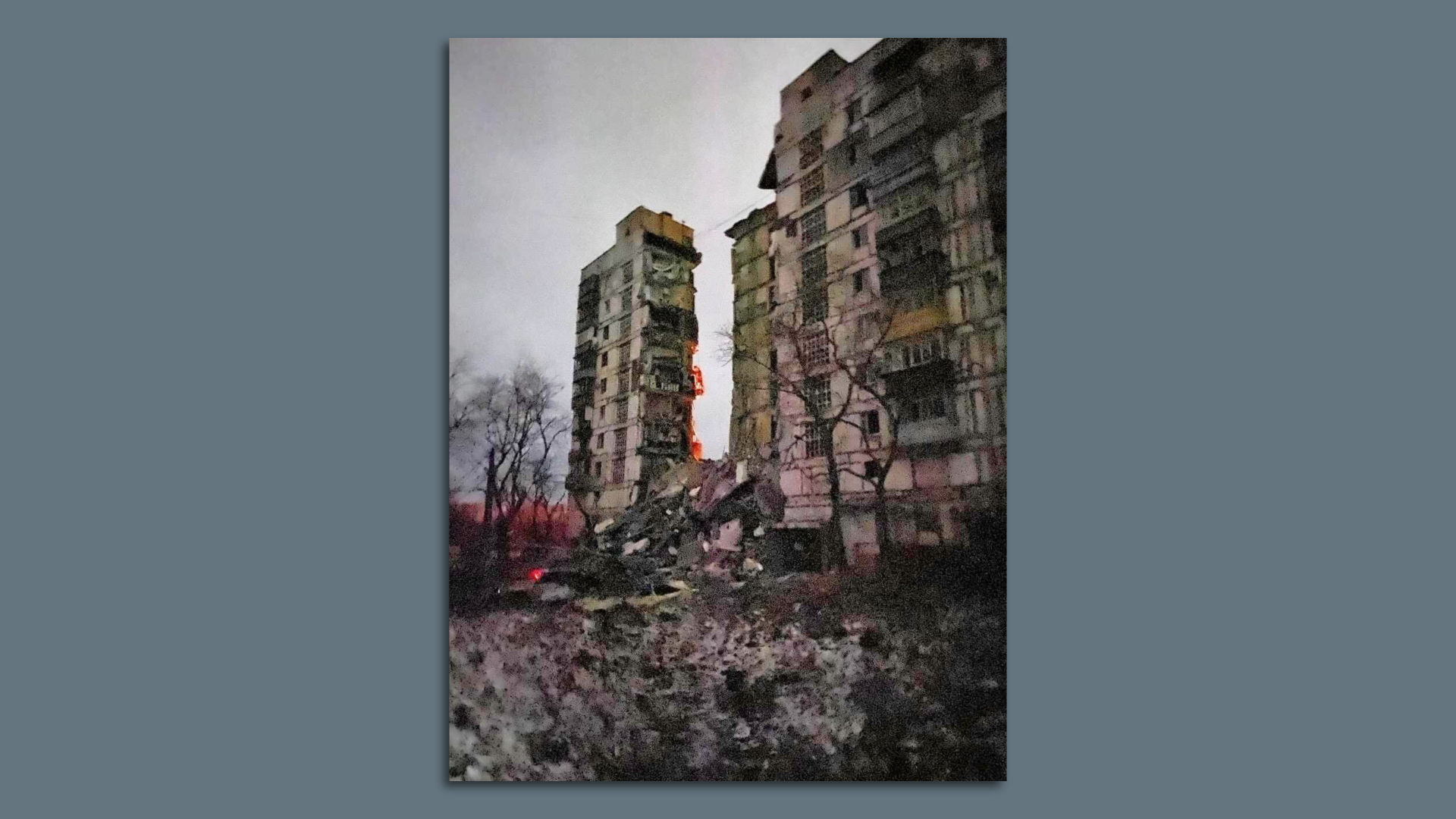

"Hell on Earth"

When the war started in February, Ulyanchenko was in his final year at Mariupol State University, studying political science.

- After weeks of bombardment, Russian occupation turned Mariupol into "hell on Earth," Ulyanchenko says. His mother had died from cancer two years before the Russian invasion, and he says his father, a factory worker, was killed by a Russian sniper during the war, leaving him to care for his 80-year-old grandmother.

After being in hiding for six weeks, Ulyanchenko and his grandmother evacuated to Donetsk.

- That is where Ulyanchenko first encountered filtration. Russian soldiers and officials weren't worried about his elderly grandmother, he says. Instead, they focused on young men like him.

- Ulyanchenko was taken to a police station, fingerprinted and interrogated. Asked where his military identification was, Ulyanchenko says he told the officials he was only a student. Fortunately, he had his student ID with him. He also suspects it helped that he was accompanying his ill grandmother.

- “She was sick at the time. We were together all the time, so I think it removed their suspicions that I might be a soldier or whatever else they thought I might be,” he says.

- He was given a verification document, and the next day Ulyanchenko says he and his grandmother attempted to cross the Russian border because there was "no other option" due to the "impossible living conditions."

The interrogation

At the border, Ulyanchenko's grandmother was allowed through but he says he and several others were taken to a room by a Russian soldier for questioning.

- During the interrogation, detainees were given questionnaires that asked what they thought about the Russian and Ukrainian governments, Russia's "special operation" in Ukraine, and Ukrainian nationalistic battalions.

- Weighing his answers so that he "could make it through this filtration," Ulyanchenko tells Axios he said that he was "neutral" on the questions about the Russian and Ukrainian governments and Russia's operation and he was critical of the nationalistic battalions.

- Inside the room Ulyanchenko was held in, there were four Russian soldiers and a man — "the interrogator" — in civilian clothes holding a baseball bat, he says, adding that a former Ukrainian soldier who looked roughed up was also detained there.

- Ulyanchenko says he was told to take off his clothes so they could check for tattoos that might indicate a military regiment (he doesn't have any). During the strip search, he says he could see the former soldier being beaten in the leg with the bat.

Ulyanchenko tells Axios that the interrogator took his phone to check all of his social media accounts while questioning him.

- When asked whether he had taken part in the 2013 protests that toppled Ukraine's Russian-backed president, Viktor Yanukovych, Ulyanchenko told his interrogator he was only 12 at the time.

- Asked if he was now a Nazi, Ulyanchenko immediately said "no."

- "With every new question, he was raising his voice at me a bit more, and this tension was growing bigger and bigger,” Ulyanchenko explains. "This was a scary experience. ... But I promised myself not to react and to do everything to make it through."

In total, Ulyanchenko says he spent about five hours, including 30–40 minutes of interrogation, in detention at the border.

- He was let through — crucially, with his Ukrainian passport — and reunited with his grandmother.

Three possible fates

Many others, however, have been less fortunate.

- A recently declassified U.S. intelligence assessment found that detainees typically face one of three fates: Some are given documentation and allowed to remain in Ukraine; others are forcibly deported to Russia for additional screening; and "those deemed most threatening" are likely detained in prisons in eastern Ukraine and Russia, "though little is known about their fates."

- Oleksandra Drik, who has been documenting stories like Ulyanchenko's for Ukraine’s Center for Civil Liberties, says, "people are being treated like animals, something that you wouldn't even imagine to see in the worst movie."

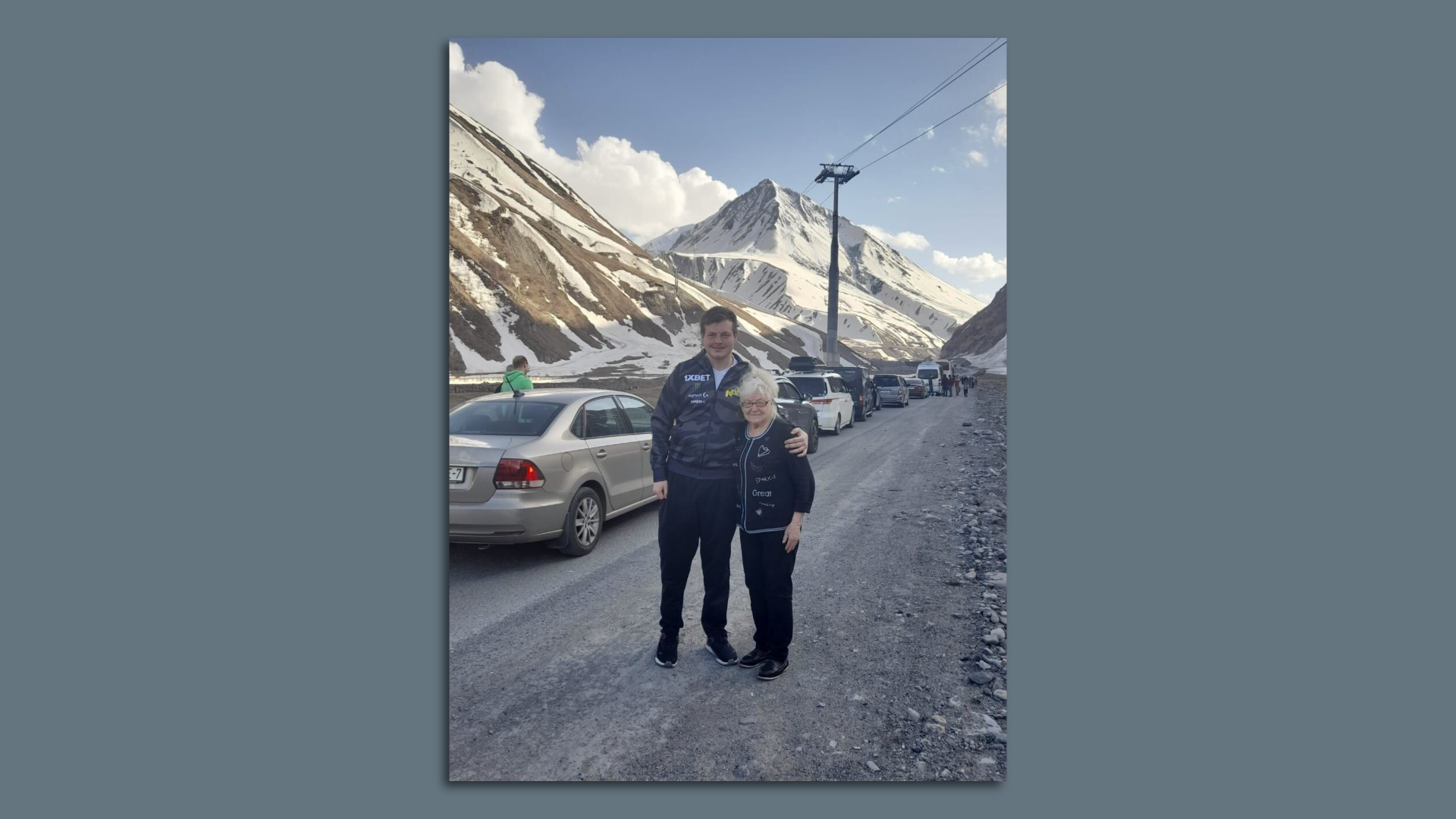

While Ulyanchenko and his grandmother felt fortunate to have gotten through filtration, their journey was far from over.

- Some of their Russian friends drove the pair to a nearby town. A few days later, they took a 13-hour train ride to the south and then another train across the border to Tbilisi, Georgia. From there, they flew to Turkey and, finally, to Germany, where they continue to live today.

Russia expanding filtration

The declassified U.S. intelligence assessment found that there are at least 18 filtration centers in eastern Ukraine and western Russia, though it noted there are likely others. Russia is scaling up the operation.

- Russian officials have frequently branded Ukrainian soldiers, particularly anyone affiliated with the nationalist militias, as terrorists.

- Moscow claims the forced deportations are humanitarian evacuations. The Russian Embassy in Washington, D.C., did not respond to a request for comment

- A U.S. State Department spokesperson said it was supporting Ukraine and the international community's efforts to "collect, document and preserve evidence of atrocities" in Ukraine. “Accountability is imperative. ... We are dedicated to holding perpetrators of war crimes and other atrocities accountable.”

For Ulyanchenko, he thinks the filtration process and the documented abuses will only end when the war ends.

- “They don’t treat people like human beings,” he says. "The Western world — and the whole world actually — should not look for excuses for Russia’s actions."

Go deeper... On the front lines in Donbas: One Ukrainian soldier's story