The global parental leave paradox

Published Date: 1/18/2020

Source: axios.com

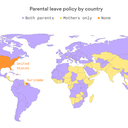

Reproduced from World Policy Center; Map: Axios VisualsParental leave is steadily becoming ubiquitous around the world, but workplace cultures in many countries continue to prevent employees — especially fathers — from taking time off.Why it matters: Paid leave not only benefits families but also makes people more likely to re-enter the workforce, experts say. And in the U.S., as the labor market tightens, robust time off policies for new parents is emerging as one way to attract talent.What's happening: While the U.S. is an outlier, other developed nations in Europe and Asia do offer extensive leave. Still, there's a gap between passing laws and actually getting people to take the time off.Often firms in the U.S. and elsewhere stress "putting the company above all else," says Kate Weisshaar, a professor at UNC, Chapel Hill. "The culture of a workplace can contribute to who feels like they're safe to take leave or take full leave."Just this week, Shinjiro Koizumi, a popular Japanese politician, made a splash when he decided to take paternity leave. New fathers get up to a year off in Japan, but only about 6% of eligible men working at private firms took it in 2018, per the New York Times.In a recent study, Weisshaar tested employer perceptions of parental leave by sending three types of resumes and cover letters for open roles: people who currently held jobs, people who stated they were unemployed due to layoffs, and people who said they had chosen to stay home for a while to take care of children.The resumes of the stay-at-home parents performed more poorly than those of the unemployed applicants, she says. And fathers were less likely to receive callbacks than mothers. "That sends a pretty strong message that employers care about this."The big picture: There's a strong economic case to be made for parental leave — and paternity leave specifically, Barrons' Matthew Klein writes.The wage gap between men and women is exacerbated by the fact that mothers are expected to take time away from work and care for new babies alone. We could chip away at that gap if men and women received the same amount of leave, Klein notes.And in a new working paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research, economists studied how parental leave in Denmark — which has one of the most generous policies at 52 weeks of paid time off — affected companies' bottom lines and found no economic impact. It's worth noting, though, that the researchers did not examine the cost of paid parental leave to the government.The bottom line: "The culture of being family friendly is one of the amenities of a job," says Heather Royer, an economist at UC, Santa Barbara, and one of the authors of the NBER paper. "Having family leave and having people take it creates this feeling that the firm values like outside of work, and that can make people happier when they're working."Go deeper: Corporate America is pressured to boost paid parental leave